By William Milliken

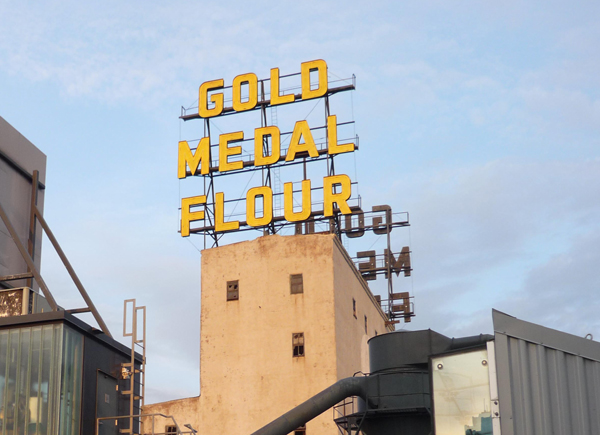

It’s easy to find the Mill City Museum. Just look beneath the Gold Medal Flour sign on the west side of the Mississippi River in downtown Minneapolis. As I approached, in 2005, the old limestone walls of the Washburn Crosby A mill containing the museum within their shell, I could feel the goose bumps starting. This was where it all began. On Wednesday night Sept. 23, 1903 close to 1,500 Washburn Crosby Co. Employees walked out, past a notice that “All employees of this mill leaving their positions are discharged and are no longer in the employ of the company.” Executive William Dunwoody vowed to “fight until the finish”. The company would never negotiate with a labor union. Minneapolis would never be the same.

As I crossed Second Street toward the museum entrance I could almost hear the pounding of the hammers erecting a huge stockade fence around the milling district as over a thousand pickets shouted “scab” and threw the occasional brick. It was immediately clear that Dunwoody and company president James Stroud Bell intended to end the evil presence of unions in the mills. In order to neutralize the surprisingly effective shutdown the company outfitted a vacant Pillsbury oatmeal mill to house and feed over eight hundred nonunion replacements that were smuggled through the picket lines in heavily guarded carriages. In a battle of attrition the under-funded union gradually crumbled. On October 8, 1903, an unnamed miller told the Minneapolis Tribune that the “backbone of the strike is broken, and there will be nothing more doing in the way of strikes for some time.” Although a few strikers would be rehired “the orators, organizers and agitators were not wanted.” This would be the policy in the mills for the next thirty three years. A faded Gold Medal Flour sign on the east side of St. Paul, photographed in 1981 by Bruce White

Ridiculous, you say? Not at all. On April 11, 1919 the National War Labor Board ruled that the Minneapolis mill companies had to bargain collectively with organized employees. Two weeks later Pillsbury and Washburn Crosby set up a new committee system. Employees would elect representatives to meet with company directors to discuss any issues involving their work. Employees were also sent an “Industrial Creed” that announced that “Labor and Capital are partners, not enemies.” The Minneapolis Labor Review recognized a company union immediately and expressed great surprise “that suddenly the great milling corporations are taking a deep interest in their welfare.”

Jean Spielman, organizer for Local 92 of the flour mill workers union, explained the nature of the deception to large labor rallies. The company committees would advise the company but had no power whatsoever. Faced with an educated and skeptical workforce, Washburn Crosby created The Eventually News (meaning that someday it would actually report the news?) to promote employee loyalty. In addition to sports and holidays, however, the paper reported on the joint conferences between executives and the committees. The paper was a dismal failure. In a July 1920 election only 321 Washburn-Crosby employees out of 1,400 voted for committee representatives. Pianos and tanning parlors had received a stony thumbs down.

John Crosby had had enough. The con job had failed, it was time for the dirty tricks department. The Marshall Service of Kansas City was hired to plant undercover detectives in each plant at a cost of $10,000 per year. The agents rapidly befriended union organizers and officers. Once inside Local 92 they relayed lists of union members to Pillsbury and Washburn Crosby. While the companies slowly found excuses to fire union members the fourteen agents discredited union leaders and encouraged conflict among various factions within the union. The coup de grace came in August of 1921 when one of the detectives was elected secretary of the union. The Marshall Service inquired if the mills wanted the union completely destroyed or wanted its agents to control it in a weakened state to forestall outside organizers. The millers enthusiastically endorsed the second option.

But these weren’t the only detectives in the flour mills. The Citizens Alliance, heavily funded by Pillsbury and Washburn-Crosby, started a Free Employment Bureau in 1919 to supply Minneapolis industries with nonunion workers. To get a job selected workers were required to report on union activities at their job sites. Very crude, according to Luther Boyce of the Northern Information Bureau. Boyce’s more “professional” agents had infiltrated the Industrial Workers of the World and sold his intelligence to the millers and to other industrial subscribers. There were also the forty six agents of the Committee of thirteen that were funded by the same companies and the…. You get the picture. Was one of the mill girls a spy? Perhaps a better question would be, would the mills allow any workers to cavort without keeping an eye on them? Very unlikely. Not exactly the happy family reported in The Eventually News or presented in the museum exhibit.

I stumbled slightly as a college-aged foreign exchange student bounced off my shoulder on his way around a cool looking piece of mill machinery. I’m a sucker for antique machines, particularly when the long belt drives are running. I followed him to two small antique roller mills standing placidly as if waiting for a power belt to engage. It’s hard to imagine such small machines revolutionizing an industry and feeding a nation. My eyes strayed toward the small kids frolicking in the water lab and there, down at knee level on a small display board was Jean Spielman! I couldn’t believe it. I had to crouch down to read the 1920 quote, “It is a sad commentary upon civilization that an industry flourishing to the extent as the flour milling industry is, that the workers are the most underpaid next to the steel industry. The twelve hour day is still a fact in many a flour mill in the U.S.” Below this industry spokesman William Edgar insisted that wages in the mills had “advanced steadily since the outbreak of war.”

A very short note beneath these quotes explained that the flour packers struck for higher wages in 1917 and soon afterwards most Minneapolis mill workers joined Local 92. And that’s all folks. That’s the one and only mention of a union in the Mill City Museum. Without any further discussion the museum visitor can only conclude that Washburn Crosby was forever more a union shop. Of course, one year later the union was a mere shell controlled by company spies. Upstairs the gift shop sells copies of Mill City, a book that was produced to complement the museum. Here we learn that “By 1921 the union was in tatters. . . .” Why did museum curators decide to eliminate this simple explanation? Jean Spielman and the members of his union knew what was going on in 1921, so why is this knowledge denied the museum visitor in 2005? Spielman wrote that “the stool pigeon is to be found everywhere a union is contemplated among the employees of a mill.” Washburn Crosby and the Citizens Alliance may have defeated Spielman but they certainly didn’t fool him.

It was time for my Flour Tower tour. I wound my way between a huge harvest table and several General Mills product displays. One featured the 1991 Twins World Series wheaties box. I wedged myself into the top corner of a huge freight elevator above a twitching, squirming bunch of school children. The wooden slat doors slapped together and the elevator started slowly rising. Each floor had been cleverly designed to represent a floor in a working mill. With a loud whirring noise the belts began to move, the machines came to life. A collective ooh escaped the from the kids. This was very cool.

We finally stopped at the seventh floor where the doors opened to reveal the mill manager’s office, recreated in great detail. Right down to the production schedule and engine schematics. The back window filled with panoramic views of the Minneapolis milling district as a sonorous voice told us “the mills stood at St. Anthony Falls in their corona of flour dust like blockhouses guarding the rapids of the river.” The screen dissolved into golden wheat fields as a pompous Chamber of Commerce voice asked, ”Where is a market to be found for all this flour? The answer is, the world is our market.” The jaunty westward ho sound of Copeland’s Rodeo played in the background.

It was just like one of those old industrial propaganda films I used to watch in grade school. I’m embarrassed to say that I was the nerdy kid that knew how to thread the 16-mm projector so I saw a lot of these hideous things. Forty years later I discovered that many of them had been produced by the National Association of Manufacturers public relations department under the direction of Harry Bullis of General Mills. The same Harry Bullis who started his career working on The Eventually News. In both cases, the propaganda was intended to promote free enterprise and suppress unions and radical political movements.

On the way back down the elevator stopped at several different floors where mill equipment was whirring away. The voices of real workers told us about production quotas, returning servicemen taking women’s jobs, unsafe working conditions and finally the day the plant shut down with no warning. Real workers with real problems, this was good stuff. On the final floor the designers had simulated an engine fire that flashed and roared. After an extremely loud dust explosion the set went dark. Several small children in front of me sobbed in terror.

The flour tower deserves its various awards. The realism of the sets and the sincerity of the workers voices was riveting. But what did the workers do about all these problems? Did they join a union and negotiate for improvements? The curators never seem to grasp the concept of a working class. They found the workers, but they treat them all as individuals. Their only unity is their function in the complex machinery of the mill. They are never allowed to join together, to become a working class, to join a union. As I stepped off the elevator it hit me. It wasn’t just the newsreel, the entire museum was a sort of industrial propaganda stage set. With a little modern public relations thrown in.

How and why had the antiunion activities of the Citizens Alliance and the struggles of Minneapolis workers to organize unions been rejected by the museum curators? Fortunately in 2005, I was writing an article for a respectable local publication. Doors opened, before I knew it. I was getting a behind the scenes view of the flour tower and long interviews with head curator Kate Roberts and Minnesota Historical Society Director Nina Archabal, two very smart, smooth and enthusiastic supporters of the Mill City Museum. I was also given planning documents for various stages of museum development. In August of 2000 the St. Anthony Falls Heritage Center plan included a labor exhibit which included a hiring hall, a speakers corner and text on immigration, the Cooper’s Union and women workers—Unfortunately, no Citizens Alliance, and without them you can’t really tell the history of class struggle that created our unique Minnesota heritage. What happened to the labor exhibit? A round table discussion with selected scholars urged “the team to cut back the number of topics covered in the exhibits, and to focus interpretation on stories more directly related to the mill building.” The enlightened team now concentrated on the forces that fed Minneapolis’ emergence as the Mill City: Power, Production, Promotion and People. The four Ps. Caught in the strainer of this gibberish, labor was discarded.

I asked both Kate Roberts and Nina Archabal who decided not to have the Citizens Alliance in the museum and when it was decided. Kate couldn’t remember. It had been a long and very fluid process, and she couldn’t remember anyone ever talking about the Citizens Alliance. They, of course, knew all about the Citizens Alliance. MHS had financed a decade of research on the employers association and then published my own book A Union Against Unions. MHS Press promotional material says that the “Citizens Alliance in reality engaged in class warfare. It blacklisted union workers, ran a spy network to ferret out union activity, and, when necessary, raised a private army to crush its opposition with brute force.” In my conversation with her in 2005, Nina Archabal deflected the question, indicating that these were curatorial decisions. “The museum was Kate’s baby,” she said.

These were the people that had to know the answer, but they were suffering from collective amnesia. This was even better than Nixon or Bush in the logic department. How could you remember deciding something if you never even considered it? What did George W. Bush call this? Disassembling.

That day of my first visit to Mill City Museum, as I walked back through the museum I noticed a plaque with the Mill City Museum motto written on it. Whoever you are, wherever you’re from, what happened here continues to shape your world. Too True! The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance, forged in the 1903 mill strike, still exists in 2005. The organization was renamed Associated Industries of Minneapolis in 1937 and became Employers Association, Inc. in 1985.

How does this organization continue to shape our world? Through its labor relations membership services it still manages a war, albeit a more subtle war, against labor unions. In 1994 it led the court battle to protect the right of Minnesota businesses to replace union employees during a strike. This, of course, has led to the decertification of numerous unions. The 1939 Minnesota Labor Relations Law, written for Associated Industries by the lawyers of the Minneapolis law firm Dorsey and Whitney (which coincidentally has long done legal work for the Minnesota Historical Society), is still used to restrict union activities. The Taft Hartley Act, which was modeled after the Minnesota law, still suppresses the organization and spread of labor unions across the country.

And who belongs to Employers Association Inc.? As of 1997 the membership included General Mills, Dayton Hudson, Norwest Corp. In short, many of the companies that formed the Citizens Alliance in 1903, lost the Battle of Deputies Run in 1934 and rewrote U.S. Labor laws after the depression have now paid for a museum that just happens to totally ignore the legacy of class warfare that they created. And it gets even stranger. The primary fund raiser and, according to Nina Archabal, the inspiration for the entire museum was David Koch, President of the Minnesota Historical Society. Mr. Koch (who at least is not that David Koch, the well known funder of conservative causes) was formerly the CEO of Graco, an important donor and a member of Employers Association, Inc.

In the end, of course, responsibility is not the important issue. The Mill City Museum now exists beneath the Gold Medal Flour sign, inside the crumbling walls of the Washburn A Mill. But where are the men and women who struggled for economic justice while they built Minneapolis stone by stone? Many of them fought and bled on our streets in a desperate attempt to establish a decent life, a life beyond brutal servitude. Don’t they at least deserve to have their place in history? “Museums change,” Director Archabal told me, “new exhibits will be developed. If we discover that we’ve left something out we can go back and take another look at it.” The Working Class is waiting.

*********

Seven years after my first visit to Mill City Museum I went back to scour the mill city museum again searching for the working class. The museum exhibits have not changed. The new exhibits mentioned by Nina Archabal have not been developed. The Flour Tower extravaganza also remains unchanged. MHS curators presumably have yet to perceive any need for improving their award winning production.

However, to at least succeed in entertaining visitors in our oh-so-modern hyperactive world they added a frenetic wacky video by Minneapolis humorist and writer Kevin Kling, “Minneapolis in 19 Minutes Flat.” Determined to see everything I very reluctantly followed a large group of fidgeting children—squirming children are the mainstay of MHS museums and historic sites—into the theater. Apparently conceived of and made for either squirming children or adults with exceedingly short attention spans, the show careens through history with dizzying speed. Pop-up cut outs, Kling in an endless parade of period costumes, and the live shrieks of tethered children complete the disorienting experience. Although I’m a fan of Monty Python and Fawlty Towers, I like my history slow, detailed, and serious.

As the 19th and 20th century flashed by I almost missed the best “bit.” Refocusing on the screen after a brief glare at the writhing grade-school child next to me, I was amazed to be watching a newsreel clip of the 1934 Teamsters strike. The voice-over mentioned the long years of struggle between the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and the union as National Guard troops scurried across the screen. The voice announced a union victory and then we were swept on to the next frantic event.

Perhaps in the world of museum speak this forty-second “bit” is considered an adequate presentation. This is, after all, an industrial museum and workers are well, just workers. They aren’t the founders of the city that are endlessly written about and glorified in history books and museums. In order to build great mills and buildings, however, the founders had to control what happened in the city. This is an important part of the Recipe for a Mill City. The founders of the city of Minneapolis spent vast amounts of time and money to control the laws, courts, police and to spy on and root out any threat to their domination of industry. They made Minneapolis into a city where the vast majority (workers) struggled to survive while the mill owners basked in a life of luxury. A city where employers profits necessitated the poverty of tens of thousands of hard working citizens. I’m afraid forty seconds doesn’t quite do justice to the complex history of industrial warfare in Minneapolis, a history that still has an impact on the lives of all working Americans.

The Working Class is still waiting.

William Millikan, a Minneapolis historian, is the author of A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903–1947, published by the MHS Press in 2001.

What an eloquent and comprehensive (within the limits of this comment space) comment by Bill, and bringing it up to the present day. He is absolutely right on.

What a lost opportunity to introduce students, including young, squirmy ones, to the true history of Mpls. and the struggle many of their forebearers endured adapting and adopting to life in a growing metropolis where they were considered fodder for its growing industries.

The influence of money and power on historically accurate history is a constant one, and I don’t know how it would ever be resolved. Few individuals or organizations have the money to help record history through buildings, like the Mill City Museum, or books and magazine articles about the company and/or its founders. The alternative is that nothing would get built or written at all without this infusion of funds. I suspect that is true of the Mill City Museum. It would not have been built if the Historical Society had in one way or another been influenced by those still-active corporate powers that “built Minneapolis.” It would not have been built if those who created the exhibits had told the truth as Bill Millikan has. There are other situations where books or magazines got published only because the subject or subjects – businesses, business leaders, industries–put up the money. Did they then chastely keep their hands off the finished product book or museum? I don’t know.

I think no one influenced Folwell much, and many historians have had no untoward influence on historical projects. But I think more and more, history only gets done with funding from the very people and institutions that are the subjects of projects.

Many thanks to Bill Millikan for this long, perceptive, and sensitive look at the Mill City Museum. And thanks to Bruce White for providing a venue. It is a truism of history that the story of the past is told by the winners, and there is not much question in today’s U.S.A. about who the winners have been.

Yet, as Ginny points out, Minnesota has been fortunate in preserving at least some small amount of balance in the telling of its story. Folwell lays out with unvarnished bluntness the way in which its great lumber fortunes were built by stealing state-owned and Indian-owned timber; books like Bill Millikan’s history of the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance have been published; collecting projects like Carl Ross’s effort to preserve the nearly buried evidence of radical movements have been carried out.

That said, the story of Minnesota’s working class has not been told. The record is full of promising projects that never were finished. I am thinking of books by Hy Berman and Tom O’Connell among others. Some still may be produced, but does anyone even remember the decades-long effort by Russell Fridley and Dave Roe to find funding and support for a museum of Minnesota labor history?

Rhoda

I don’t remember that, but I’m certain it would never get funded today.